Not long after educator Tikisha-Michelle Johnson and her family moved from Dallas to the Wilmington area about six years ago, they decided to attend an outdoor concert at Mayfaire Town Center.

“Wherever we move, I always try to get involved,” said Johnson, whose husband’s company had transferred him here. “So we went to the concert, and I thought, ‘Oh, this is going to be great … We’ll go out here, we’ll sit and we’ll meet some people and see people.’”

Then she began to scan the crowd. On the surface, there appeared to be only one other person of any possible African American descent that Johnson could see.

“I didn’t see anybody even very tanned,” she said. “And so I was like, ‘This can’t be a thing.’”

Johnson, the founder of Wilmington-based nonprofit Education InsideOut, had previously lived not only in Texas but in other states, including Arkansas, Alabama and Illinois. In a community outside Dallas, she taught at a school that had 33 different cultures represented in one building.

“But sitting out there at that event, that just had me baffled,” she recalled. “I’d never experienced anything like that before in my life.”

Anecdotal and statistical evidence shows that the Wilmington area is, in many ways, a segregated city and region, where the business community in particular is noticeably lacking in African American professionals.

Those who are working to address the issue point to federal statistics: 18% of Wilmington’s population is African American and nearly 77% white, but the poverty rate among African Americans in the Port City is 41%, according to the Census. In North Carolina, the population is about 71% white and 22% African American, and the poverty rate among African Americans statewide is about 25%

The local disparity is an issue that both white and black businesspeople, and others, are discussing, studying and working to do something about.

Rooted in the Past

Wilmington is not the only city in America that struggles with diversity issues. But it is likely the only city where a violent race riot came with a coup d’etat.

Tracey Newkirk, business owner and chairwoman of the African American Business Council, describes when that coup happened, in 1898, as “The Year of the Intentional Divide.”

The episode has also been referred to as the Wilmington Massacre, Race Riot or Insurrection of 1898.

“It was the darkest period in Wilmington’s history,” Newkirk (who recently changed her last name from Jackson after getting married) said during

a presentation at the Wilmington Convention Center last year.

She was speaking to a mainly white audience of more than 400 businesspeople at a Greater Wilmington Business Journal Power Breakfast. “The ramifications of this type of intentional divide do not go away with the passage of time or because we don’t talk about it,” Newkirk said. “The aura, the feeling, the vibe of this type of intentional divide still lingers in our community today.”

Wilmington looked completely different more than a century ago in the era after the Civil War, when more than 50% of the Port City was made up of African Americans.

“During Reconstruction, African American people were able to thrive because there were social support systems helping to create communities and business opportunities and political empowerment,” explained Kim Cook, a professor of sociology and criminology at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. “And then after Reconstruction ended, there was a violent turn to continuing suppression of African American people, and that hasn’t fully ended.”

In November 1898, a group of prominent white residents in Wilmington forcibly erased what had been a thriving black middle class and overthrew a government that included a number of black elected leaders, a traumatic episode that was hushed up in subsequent years.

After the 1898 coup, there were no consequences for the perpetrators for the slaying of black residents, the theft of black property and businesses and the burning of the offices of The Daily Record, the city’s black-owned newspaper.

“The first time I really even found out about it as a person who grew up here was when I was at UNC Wilmington in a Cape Fear history class,” Wilmington Mayor Bill Saffo said. “So I was 19, 20 years old before I even knew anything about the incident … It was definitely covered up, and it was definitely not talked about. But it definitely had a significant impact on the community that is still felt today.”

Turning the Tide

But Newkirk, owner of consulting firm u-nex-o!, and others in Wilmington, including some white leaders and employers, are working to change that vibe.

Newkirk, who grew up in Leland and previously worked as director of talent acquisition and strategy for Verizon Wireless, left and then returned to the Wilmington area for the second time a few years ago.

“I felt like there was more of a solid African American leadership in the community (before she left in 2007), and then when I came back, I couldn’t find that leadership,” she said. “I didn’t see a lot of African Americans at networking events. That’s when I met Natalie (English, president and CEO of the Wilmington Chamber of Commerce), and I asked her, I said, ‘Natalie, what can I do to help more African Americans understand the economic impact and the benefit of being part of a chamber of commerce and networking as a whole?’”

That was in 2017. Around the same time, Newkirk also had an experience with her youngest son, then 24 years old, that she described as heartbreaking.

“He was like, ‘Mom, Wilmington isn’t somewhere I want to live. I don’t like it. I don’t like the vibe.’ And that bothered me,” she said.

Newkirk shares that story during her presentations on intentional inclusion.

“Unfortunately me and so many blacks like me know what he felt. It was the lingering effect of the vibe of the intentional divide,” she said in December. “So again I ask you: Help me create a Wilmington where it’s not so difficult to be black and raise a family. Help me help those individuals who find it so difficult to be part of this community, they’re ready to pack up and move to more inclusionary towns.”

The local real estate industry is an example of one that seems to be lacking in minority practitioners.

“It’s been that way for a while,” said Jonathan Barfield, who is African American, a Realtor and owner of Barfield and Associates Realty. He also serves as chairman of the New Hanover County Board of Commissioners. “I was president of the board (of Cape Fear Realtors) in 2007, and I think we may have had 15 minority members then, 15 out of 2,200. There’s just never been a large percentage of minorities in this field in Wilmington.”

But it’s not just in real estate, Barfield said. That’s why some employers are working on the issue.

In the spring, Wilmington headquartered-Live Oak Bank started roundtable discussions about recruiting a more diverse workforce, attended by 25 to 30 representatives of the largest employers in the area. Those employers include New Hanover County, the city of Wilmington, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington Health, PPD, GE, Corning and more.

“We said, ‘We’re not the only employer in the lower Cape Fear region looking at this and trying to make the region more inclusive, more attractive, more welcoming to diverse workers,” said Courtney Spencer, the bank’s chief administrative officer, about why the discussions started.

The conversations allow employers to share best practices for recruiting African American workers and other minorities.

“If you don’t have those conversations, you can’t clearly identify the needs,” Spencer said.

Lack of Contracts

The Wilmington chamber’s African American Business Council’s vision statement involves “strategically positioning black businesses for inclusion and success,” with one area of emphasis labeled “contracts of all kinds.”

At a summer meeting (

shown above) of the AABC, which started last year, the group discussed government contracts and the certification process to receive designations such as that of a Historically Underutilized Business (HUB), the separate Minority Business Enterprise (MBE) or Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE), and other programs.

“I just struggle philosophically with the whole concept of it because to me it’s just another barrier to keep you out,” Newkirk said to the group, referring to the hoops a business owner has to jump through to receive the designations.

Time is a major factor for some black-owned businesses. Entrepreneur and Burgaw native Girard Newkirk, husband of Tracey Newkirk, said that can be especially true in the case of a startup like the one he’s founded, KWHCoin, a firm that merges cryptocurrency and renewable energy to provide affordable energy access.

Startups have limited resources, said Girard Newkirk, who recently returned to the Wilmington area from California.

“You have to choose: Are you going to go fill out papers all day for a six-month process (to be certified), or are you going to go try direct marketing?” Girard Newkirk said. “I’m an entrepreneur, so I’ve been in this world for a little while, and this is one of the reasons why I had not gotten DBEcertified. It just doesn’t marry up with your balance sheet. … You have to choose between eating or filling out paperwork, literally.”

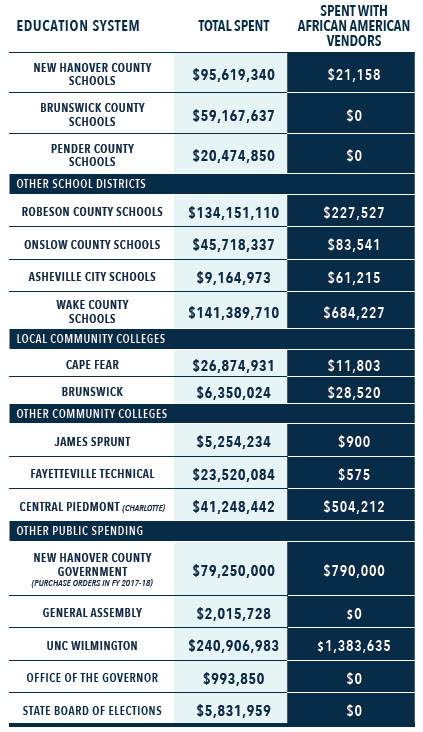

Some public institutions submit reports to the state’s HUB office showing how often HUB-certified businesses get public money. Those include local governments and agencies.

The New Hanover County Schools HUB reports show a decline in spending on goods and services with blackowned, HUB-certified businesses in the past three fiscal years, from a high of about $95,600 out of nearly $379 million total to a low last fiscal year of about $21,000 out of $95.6 million.

“We do have some minority businesses that do work for us, but they’re not certified through the HUB office, and if they’re not certified, then it doesn’t go on the report,” explained Eddie Anderson, assistant superintendent for operations for New Hanover County Schools.

He said the schools are working with Justice NC and Legal Aid to schedule an open house in January that includes a HUB office representative. “Having someone here that could help explain the process and getting them help in getting certified, we think, would be a big plus, and then we’re also going to kind of reach out to maybe banks or lending institutions and insurance agencies,” he said, “because I think that’s a challenge for minority businesses sometimes.”

And though she sometimes sees certifications as more hoops to jump through, Tracey Newkirk said at the AABC meeting in July, “Right now, this is the game we gotta play.”

Opportunity & Wealth

Dianne Jinwright, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who has a doctorate in strategic leadership, is also working to identify ways to help African American business owners through her role as chairwoman of the economic development committee of the NAACP’s New Hanover County branch.

Jinwright pointed to the fact that wealth can be generational, with the children of business owners having more social mobility and doing better economically. Part of that is land ownership, she said.

“A lot of black landowners die without a will,” Jinwright said. “And if they have several heirs, that property is at risk of being lost to investors or contractors who want to commercialize the property and therefore (in some cases) take it out of the hands of black landowners. The families lose many acres because they were not able to come to an agreement about what should happen.”

Other states have laws that help protect property legacies, and Jinwright said the NAACP is hoping to move North Carolina lawmakers in that direction.

Jinwright’s committee is also working on determining whether there’s a ceiling in Wilmington for African American business owners when it comes to access to capital for expansion.

National statistics show there can be a correlation between the race of potential loan recipients and lower lending rates. A report issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in August showed that sole proprietors who are African American or Latino are less likely than white business owners to have funding needs met and more likely to be discouraged from applying for credit, an American Banker article stated.

Starting Out

Wilmington-area resident Corey Scott, who is African American, has not tried to apply for a small business loan for the catering company he’s starting, but he has experienced other challenges.

Scott (

above), who works full time as a chef at New Hanover Regional Medical Center, where he’s been employed for 12 years, is working on launching On Thyme Catering.

“I think the only barrier that I have is actually reaching out to the right people,” Scott said. “When I first started thinking about doing it, I started reaching out to all the wrong people; they were just doing it for fun or as a hobby. Now I’m in the process of talking to a whole bunch of legit people, a whole bunch of different business owners, more higher-ranked people at the hospital. Now my vision is more clear on the business aspect and not just cooking.”

Some business owners cautioned him not to consider starting a business in downtown Wilmington, saying, “They don’t want you downtown.”

“I guess that’s like the hardest place to own a business if you’re black,” Scott said.

Currently, there are few businesses owned by African Americans in downtown Wilmington. Part of the problem is that many African Americans feel their presence isn’t welcome, Scott said.

Ed Wolverton, president and CEO of Wilmington Downtown Inc., said he disagrees with that perception.

“We’re open for all types of entrepreneurs,” he said.

Another issue Scott has come across is finding resources.

“People don’t tell us a lot of stuff. I’ve got to go searching, asking a million different people about it. We don’t have a ton of seminars we’re invited to,” he said. “I have to go through somebody else to invite us. You don’t have people coming to the MLK Center putting on seminars or helping people with credit.”

Still, Scott’s outlook is positive as he and his wife, Phallin, work on becoming their own bosses.

“I know a lot of people that’s trying to start here,” he said. “It seems like it’s getting bigger and bigger, the talent here.”

Working on Change

Cedric Harrison agrees. Harrison, founder of nonprofit organization Support the Port, came back to Wilmington a second time after working in Washington, D.C., and Atlanta.

Before that, just after he graduated from the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, he tried working in Wilmington, hoping to start a career in marketing and entertainment. But the only option he found was a temporary labor agency.

“I used to go out there at five o’clock in the morning with people with criminal backgrounds, with drug addictions, and here I am with no drug addiction, no criminal background and just that college degree,” Harrison said.

He could find no other opportunity in his chosen field, he said, noting “a lot of those circles are filled with people that don’t look like me,” especially at the hiring level.

“I come from an impoverished area of Wilmington, and so that’s where my network heavily existed,” he said.

But since he returned, he’s found some success with Support the Port Foundation Inc., a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, which recently received a $25,000 hurricane recovery grant.

As part of its mission to “enhance, cultivate and provide a renewed sense of community ownership” to Wilmington residents, Support the Port also aims to boost entrepreneurs, Harrison said.

“I think a lot of people already know about the problems that exist for African Americans to be successful,” he said. “My goal is to try to figure out what the solution is like. And I think we’re doing a pretty good job of that.”

Joe Finley, co-founder of Wilmington-based CastleBranch and tekMountain, believes change is possible.

He’s been hosting community forums in the Port City that highlight and examine some of the issues around inequality, including one in August on the continued influence of the Confederacy. The problem isn’t limited to Wilmington, Finley said, but it does seem more pronounced here.

“In every area, white people are succeeding more than black people, and it’s because of systems that keep black people suppressed,” he said. “I don’t know if we can change the whole world, and that’s not my objective … but we can do things to change Wilmington. We truly, truly can.”

“I just struggle philosophically with the whole concept of it because to me it’s just another barrier to keep you out,” Newkirk said to the group, referring to the hoops a business owner has to jump through to receive the designations.

“I just struggle philosophically with the whole concept of it because to me it’s just another barrier to keep you out,” Newkirk said to the group, referring to the hoops a business owner has to jump through to receive the designations. Time is a major factor for some black-owned businesses. Entrepreneur and Burgaw native Girard Newkirk, husband of Tracey Newkirk, said that can be especially true in the case of a startup like the one he’s founded, KWHCoin, a firm that merges cryptocurrency and renewable energy to provide affordable energy access.

Time is a major factor for some black-owned businesses. Entrepreneur and Burgaw native Girard Newkirk, husband of Tracey Newkirk, said that can be especially true in the case of a startup like the one he’s founded, KWHCoin, a firm that merges cryptocurrency and renewable energy to provide affordable energy access.