North Carolina’s ports are making hefty infrastructure improvements, and now they’re looking for a return on those investments.

“We’re having the largest ships that are calling on the East Coast … coming to this port. We’ve invested in new cranes. We are investing in other infrastructure that we’re able to do the same type of capabilities that these larger ports around us have – plus add on this basis of efficiency and keeping things moving,” N.C. Ports Executive Director Paul Cozza said. “One of the things that we have as a challenge – as we go around the state, as we go around the world – is advertising and marketing what our capabilities are.

“Four years ago, five years ago, this didn’t exist here,” Cozza said of the growing capabilities that have come with N.C. Ports’ capital investments.

But even with the more recent expansions, officials say the Port of Wilmington has not yet reached its full potential.

For Cozza, that presents opportunities.

The Port of Wilmington is situated on more than 280 acres south of downtown and is 26 miles up the Cape Fear River from open ocean. Its river channel depth is 42 feet, which allows some of the larger ships cruising to ports along the coast to reach the terminal. It supports cargo through shipping containers, bulk (unpackaged items), breakbulk (packaged items) and wheeled cargo.

The Port of Morehead City is smaller and does not handle containers but supports all other cargo.

Like many ports dotted along the East Coast, Wilmington’s facility has been implementing significant changes to keep competitive in the global market.

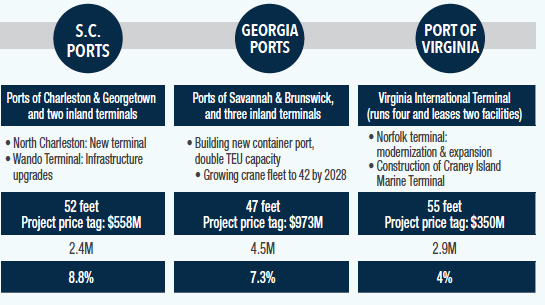

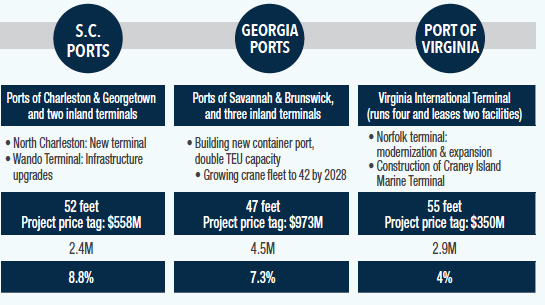

In the past two years, N.C. Ports purchased and installed three new neo-Panamax cranes at the Wilmington port as part of its $221 million capital improvement plan. Other key investments in that plan are still to come, including another potential widening of the port’s turning basin.

As of August, the port, which has had to address environmental impacts from the proposed dredging, was still waiting on federal approvals for the second phase of its turning basin project. The first phase was completed in 2016.

Port officials hope to gain approval to begin construction on the $21 million project this year, with a timeline to be complete in early 2020. The project would involve widening the Cape Fear River just north of the port to over 1,500 feet so that larger cargo ships could turn around and head back to sea.

Officials said the turning basin’s expansion is the final piece for the port to accommodate larger ships with the capacity to hold 14,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), an industry measurement for containers.

Should the turning basin expansion gain the necessary approval and be complete, it, along with the new cranes and berth improvements, would give the Port of Wilmington the capability to handle two, 14,000 TEU vessels at the same time.

“We’re getting there. We want to really be seen as a catalyst for economic development in the state,” Cozza said. “I think we’re seen as a partner. I think we’re seen as definitely a contributor. But I’d like it that the port is seen in the entire state as a real catalyst for economic development, and that is one of our longer-term goals.”

The capital improvements have happened since Cozza (

shown above) was named the ports’ executive director in 2014. His extensive background in the maritime industry includes his previous role as president of marine logistics company The CSL Group as well as other executive roles with The Maersk Group, a container shipping line.

The role with N.C. Ports is the first public port role for Cozza, who also served in the military.

For North Carolina, the business coming through the Port of Wilmington and Port of Morehead City contributes $15.4 billion annually to the state’s economy, with $12.9 billion attributed to goods moving through Wilmington’s terminal, according to a

recent economic report done by N.C. State University transportation researchers and commissioned by N.C. Ports.

The deep-water ports of Wilmington and Morehead City, plus the Charlotte Inland Port, are owned and operated by the N.C. Ports Authority, otherwise known as N.C. Ports.

N.C. Ports funds its operations through its own revenue stream, though it has received state funding for the capital plan projects. Its operating revenue comes to about $51 million annually, and it employs more than 200 people.

The Seascape

Business at the Port of Wilmington took a hit from Hurricane Florence last September, which port officials attribute to a 5% dip in container traffic in the 2018-19 fiscal year.

During that fiscal year, which ended June 30, the Port of Wilmington saw more than 306,000 TEUs.

The year prior, however, was a record for the facility in terms of container volume, with more than 322,000 TEUs handled at the port.

Before then, like at most U.S. ports, the collapse of major international shipping company Hanjin impacted the Port of Wilmington, which saw a sizable traffic drop off during the 2017 fiscal year before rebounding the next year by 38.6%.

With the ups and downs in recent years, traffic at the port overall has grown 2.9% between fiscal years 2015 and 2019.

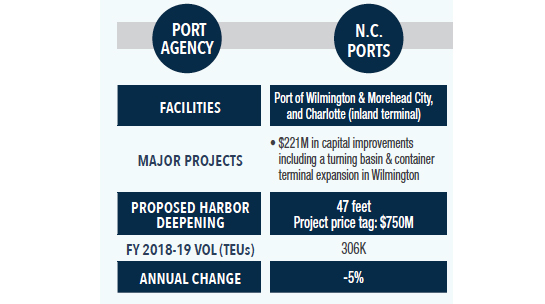

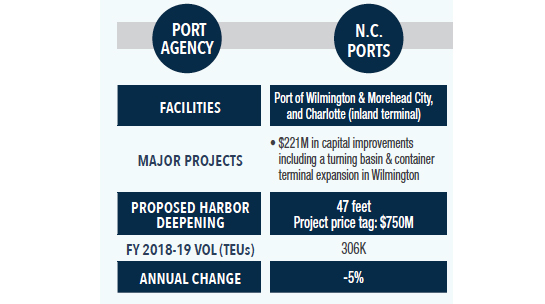

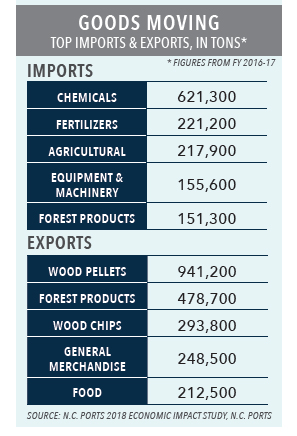

When looking at neighboring ports, Wilmington’s activity – while growing – is dwarfed when it comes to overall traffic.

Charleston reported annual container volume during the past fiscal year at about 2.4 million TEUs, while Savannah saw 4.5 million TEUs. Both have experienced record levels for their facilities in recent years.

During the 2018-19 fiscal year, Savannah’s containers grew by 7.3% and Charleston’s by 8.8%.

The Port of Virginia, which includes four general cargo facilities at Norfolk, Portsmouth, Newport News and Front Royal, Virginia, reported an overall record of 2.9 million TEUs in FY 2018-19, an increase of 4% from the previous year.

And while N.C. Ports is investing, so are its competitors.

Each is making changes to support the larger vessels traveling the Atlantic Coast, much of it sparked by the mid- 2016 expansion of the Panama Canal, where cargo ships ranging upward of 14,000 TEUs come through to get to the East Coast.

But these ships aren’t nearly the largest. Ultra-large container ships reaching more than 20,000 TEUs are sailing around Asia, some able to reach Europe through Egypt’s Suez Canal. Those ships have yet to reach the East Coast where the shipping channels are too shallow.

The Virginia Port Authority, however, aims to capture some of that business with a project to deepen its Norfolk Harbor shipping channels. Now in design, the projected channel depth at 55 feet deep would be the deepest channel on the East Coast. On top of the harbor project, it’s also expanding infrastructure at other terminals, among other investments.

Port agencies in South Carolina and Georgia are also going deeper. The Port of Charleston plans to go to a channel depth of 52 feet, and the Port of Savannah’s plans are to go down to 47 feet.

Georgia officials this month also announced plans to double the Port of Savannah’s capacity to 11 million TEUs a year and build a new container port near its existing facility.

To stay competitive with these changes N.C. Ports officials have worked up the first draft of a feasibility study to potentially deepen the Wilmington Harbor again, this time from its current depth of 42 feet to 47.

But even with the ever-growing capabilities of its neighbors, the Port of Wilmington does well to support a secondary, niche market, said Asaf Ashar, an independent consultant with more than 40 years of experience in the industry and research professor emeritus with the National Ports and Waterways Institute.

“Wilmington can survive as they do now as a niche port. They will not get the big flood of Asian imports,” Ashar said. “There is room for these type of ports especially because they are export-oriented. They support a lot of economic activities behind manufacturing, agriculture and so on.”

To justify the cost of dredging Wilmington’s access channel to 47 feet or, perhaps, expanding to the port’s available acreage in Southport, would be difficult given the port’s present market position, he said.

“It is not realistic to expect Wilmington to jump league and be in the same league with Norfolk, Savannah and New York, even with Southport and a deeper channel. There is no shortage of facilities and expansion plans in the major U.S. East Coast ports, while the market – especially the major east-west trades (such as China) on which big ships are deployed – is slowing,” Ashar said.

N.C. Ports’ 600-acre property near Southport was purchased by the authority back in the mid- 2000s for about $30 million. The authority announced plans to build an international terminal there but later dropped the project.

Though it still owns the property, the authority has no near-future plans for the Southport land, Cozza said.

N.C. Ports also owns about 180 acres outside the Wilmington terminal for future business growth, including about 90 acres off Raleigh Street and 90 acres off South Front Street just north of its existing terminal.

Aside from port land, other industrial sites in Southeastern North Carolina are being pushed as part of a local economic development model focused on reeling in business that could use the port.

The model is based on what has been done at some neighboring ports, said Steve Yost, president of North Carolina’s Southeast, an economic development agency serving an 18-county region, including the Wilmington area.

This “at-port model” implemented by local economic developers has helped land companies such as BlueArrow Warehousing & Logistics LLC and Fine Fixtures, which located to Pender County last year. It’s a marketing focus for local and regional economic developers trying to attract companies that need to be close to the port.

“We have certainly plugged that (model) fully into our marketing recruitment. And on an ongoing basis about 40% to 50% of the prospective companies that we talk to have some sort of port requirement,” Yost said.

Wilmington Business Development, which serves economic development efforts for Wilmington, New Hanover and Pender counties, is also pushing the needle on this business recruitment model.

“While our port is not as large or active as those of Norfolk, Savannah and Charleston, we are cost-competitive,” WBD CEO Scott Satterfield said. “The atport distribution model relies on ready real estate and strong surface transportation links. Those improvements have also been a game changer for us.”

PORTS OF CALL:

A glance at how the Port of Wilmington and some of its southeast competitors are changing

Vying for Markets

While size is a part of the competitive landscape, time also is a major consideration for shippers.

The Port of Wilmington’s efficiencies make it stand out among the East Coast and Gulf ports, Cozza said.

“There are congestion issues at a lot of our ports around the U.S., in the Northeast, in parts of the West Coast and other areas. It’s something that we play up on all the time,” he said. “Our service levels and the way that we’re able to keep speed, continuity and fluidity in all of our day-today operations, that keeps us very competitive.”

N.C. Ports leaders aim to compete for business both within the Southeast region and the West Coast, to capture the shift of cargo moving to East Coast ports, Cozza said.

“Our mantra is this: We have to be better; we have to be faster; we have to be of less expense than any of the ports around us for us to continue to be able to attract business. And it’s showing, and it’s a model that’s working too,” Cozza said.

Efficiencies highlighted at the Port of Wilmington include the time it takes to for vessels to move through the docks and for trucks to move in and out port gates, as well as overall customer service support, said Brian Clark, N.C. Ports’ COO and deputy executive director.

The port has one of the highest crane productivity rates on the East Coast, with more than 40 container moves per hour, he said. It also boasts 19 minutes for a truck to move in and out of the facility.

Those efficiencies could bring the port to a more competitive level, considering the time it takes for vessels to reach the port upriver. Its larger, neighboring ports don’t have the same level of travel distance to reach the docks.

“As we are successful in securing new business, we need to make sure we continue to deliver those same service levels,” Clark said.

And that ability to attract business could continue as the port sets itself up for more cargo flow.

N.C. Ports’ capital improvement plan is a multiyear project, Clark said.

The port now has its new cranes, bringing the total to nine at the port, and its berth construction is anticipated to be done by the end of the year, Clark said.

Duke Energy is also working with the port to raise power lines that cross over the Cape Fear River from 171 feet to 212 feet this year to improve the clearance for incoming ships.

And the port has made headway in its container yard construction.

“I think the most important project right now is the development of a new reefer (refrigerated) container handling yard,” Clark said. “It’s about a $15 million investment and allows us to essentially triple our current capacity for handling refrigerated cargo.”

The refrigerated container yard will grow from 300 electrical outlets and spots for containers to about 1,000 when the project is completed, which is slated for the beginning of next year, Clark said.

Construction on the Port of Wilmington’s new terminal gate area also will begin next year, and at the same time, it’s investing to upgrade the port’s terminal operating system.

“After that we’ll be slowly repaving certain parts of the yard, redeveloping smaller footprints within the facility as capacity allows. Ultimately, our goal is to double the capacity of the facility, but it will be done in line with opportunities as they present themselves,” Clark said.

The port wants to grow capacity from about 600,000 TEUs on an annual basis to ultimately 1.2 million TEUs. That will happen within the port’s current 284-acre footprint.

The port expects all terminal upgrades to be completed by 2023, Clark said.

Growing Business

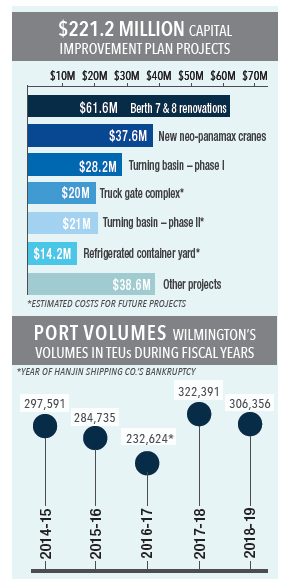

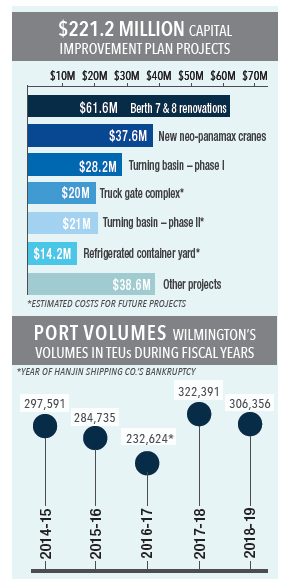

On top of expanding its ability to handle more cargo, the Port of Wilmington has opened up for more refrigerated products after it was approved for both phases of a USDA program that allows for more produce imports.

The port also leases just over 4 acres to the 101,000-square-foot, privately owned Port of Wilmington Cold Storage facility.

An on-site cold storage facility brings down the costs of logistics and takes away some of the dangers of trucking product on the road, said Chuck McCarthy, president and CEO of the facility. McCarthy is a partner in the business along with real estate developer Chuck Schoninger, who spearheaded its development.

The facility opened just weeks before the collapse of Hanjin Shipping Co. in 2016, but has been steadily gaining business each year, said McCarthy (

shown below).

The year after Hanjin went bankrupt, the cold storage facility handled 304 containers in its first full year. That increased to nearly 1,100 containers in 2018. And through May, the facility handled 659 containers, McCarthy said, adding that he expects this year’s volume to surpass 2018 levels.

Big business at the cold storage facility comes from pork and poultry producers, as well as others in agriculture.

That market is among some of the niche exports at the Port of Wilmington, said Hans Bean, senior vice president of business development at N.C. Ports. The port also serves niche imports in the textile and apparel, and furniture industries.

The port has added to the roster of shipping companies that call on the facility and its scheduling over the years. As of August, the Port of Wilmington was serviced by 10 shipping companies touching six cities in Asia, two in Europe and up to 16 throughout Central America and the Caribbean.

“I think this market can support a tremendous amount of growth … I think what the port can do will become more visible over time as it becomes more connected in the global market, on the landside and intermodally,” Bean said.

Client input sparked the port’s recent add of a next-day service through the Queen City Express, which is operated by CSX. The intermodal rail service connecting Wilmington and Charlotte was activated in 2017 and was the first such service connected to the Port of Wilmington in 30 years.

The Carolina Connector, another intermodal transportation facility that began construction in Edgecombe County this year, could be brought onto the playing field in the future. Port officials are waiting to see what capabilities that might bring.

“In some ways it’s a challenge, because historically, we’re playing catch up on our connectivity,” Bean said. “But I think also we’re very close to the customers that are using Wilmington.”

The more the Port of Wilmington can service the entire portfolio of needs for its clients, the more success the port will have in the future, he said.

“As we’re able to bring new freight in, we’re able to service the customer better,” Cozza said. “It’s not just to push volume through for the sake of pushing volume through. It’s pushing the volume through so that we’re helping an importer or exporter, especially around the state, be able to run their business more efficiently … Because at the end of the day, if we’re doing our things right, we’re improving our economic contribution numbers.”

N.C. Ports leaders aim to compete for business both within the Southeast region and the West Coast, to capture the shift of cargo moving to East Coast ports, Cozza said.

N.C. Ports leaders aim to compete for business both within the Southeast region and the West Coast, to capture the shift of cargo moving to East Coast ports, Cozza said. The refrigerated container yard will grow from 300 electrical outlets and spots for containers to about 1,000 when the project is completed, which is slated for the beginning of next year, Clark said.

The refrigerated container yard will grow from 300 electrical outlets and spots for containers to about 1,000 when the project is completed, which is slated for the beginning of next year, Clark said.